Guide to Editorial Practice

The aim of Mark Twain’s Letters is to publish, in chronological order, the most reliable and most legible text possible for every personal and business letter written by (or for) Samuel L. Clemens, and to publish the letters he received, selectively, as a part of the annotation. Whenever letters not previously included in the years published here are found, they will be inserted in their correct chronological position, and the surrounding annotation adjusted as necessary. The editorial aim for the annotation is to explain, where necessary, what the letter says and when, where, and to whom it was written, as well as how the editors have established the text published here from the relevant available documents. Apart from occasional editorial narrative inserted where there is an interval of several days with no extant letters, explanatory notes appear in the right-hand pane and are linked to superscript numbers in the text. Information about the source of the text, how the letter has been treated in the past, and how the text has now been edited (which we recognize not everyone may want or need) appears following the explanatory notes in the right-hand pane, under the textual commentary's bulleted headings.

- 1. The Author’s Signs

- Special Sorts

- Emphasis Equivalents

- 2. Revisions and Self-Corrections

- Deletions

- Insertions

- Insertions with Deletions

- 3. Emendation of the Copy-Text

- 4. Textual Commentaries

- Editorial Signs and Terms

Fundamentally, the text of any letter is a matter of historical fact, determined for all time by the original act of sending it. Its text therefore includes everything that was originally sent, from the envelope to the enclosures: all nonverbal elements, all words and word fragments, numerals, punctuation, and formal signs—whether canceled or standing, inscribed or adopted, written or stamped by others during the time of original transmission and receipt. There is no necessary or obvious hypothetical limit on which of these elements may be significant. We must begin, in fact, with the assumption that almost any aspect of an original letter might be significant, to either the writer or the recipient, or both—not to mention those for whom the letters are now being published. In principle, therefore, the text of any letter properly excludes only such additions, revisions, and corrections as were made in the documents after the original transmission and receipt—even if such changes were made by the writer or the original recipient, or someone acting on his behalf.

But while there are few limits on what properly constitutes the text of a letter, there are many limits on what constitutes a satisfactory transcription of it. Most of Clemens’s letters that survive in the original holograph, for example, lack the original envelope. Some lack one or more of the enclosures, or have been deliberately censored with the scissors, and not a few have been accidentally damaged and partly lost in one way or another, subsequent to their original transmission. All such accidents, however, limit only how much of the letter may be said to survive in its original documents, not how much of it ought to be, or even can be, part of the transcription. It is commonplace for a letter to survive partly in its original documents, and partly in a copy of originals otherwise lost: any transcription that did not rely on both could scarcely be called complete, let alone reliable. The hard question is not how transcriptions may be limited because parts of a letter no longer survive in any form, but rather what sorts of details in a letter text the editor may change or deliberately omit and still produce a reliable transcription.

We assume that the purpose of publishing letters is to make them easier to read than they are in the original documents. On that assumption, a successful transcription must include enough of the text to enable someone to rely on it, rather than the original, and it must exclude enough to make the transcribed text easier to read (or at least not more difficult to read) than the original. Thus, when the documents originally sent are intact and available, we transcribe them as fully and precisely as is compatible with a highly inclusive critical text—not a literal or all-inclusive one, but a typographical transcription that is optimally legible and, at the same time, maximally faithful to the text that Clemens himself transmitted.1 Original documents are therefore emended (changed) as little as possible, which means only in order to alter, simplify, or omit what would otherwise threaten to make the transcription unreadable, or less than fully intelligible in its own right. When, however, the original documents are lost or unavailable, we necessarily rely on the most authoritative available copy of them. Since copies by their nature contain errors, nonoriginal documents are emended as much as necessary, partly for the reasons we emend originals, but chiefly to restore the text of the lost original, insofar as the evidence permits. The only exceptions (each discussed below) are letters which survive (a) only in the author’s draft, (b) only in someone else’s paraphrase of the original, (c) only in damaged originals or unique non-originals, and (d) in originals that, wholly or in part, can be faithfully reproduced only in photographic facsimile. Whether or not a letter survives in its original documents, every departure from the text of the documents used (designated the copy-text) is recorded as an emendation in the textual commentary for that letter, barring only the most trivial kinds of change, which are instead categorized and described here.

We first applied this basic rationale for emendation in 1988 (Mark Twain’s Letters, 1853–1866) while also deploying a new system of manuscript notation. We called the result “plain text,” partly to denominate its straightforward clarity, but partly also to distinguish it from the two alternative methods commonly used to publish letters, so-called “clear text” and the now much rarer “genetic text.”2 We require two things of every transcription in plain text: (a) it must be sufficiently faithful to the text of the letter to serve as the most reliable substitute now possible for it; and (b) it must be easier to read than the original letter, so long as its reliability is preserved intact. To the extent that maximum fidelity and maximum legibility come into conflict, this way of linking them ensures that neither goal is maximized at undue expense to the other. The linkage works well for Clemens’s letters, in part because they (like many people’s letters) were intended to be read in manuscript, and his manuscripts are typically very legible to begin with. But in no small part, the linkage succeeds because the new system of notation is able to make legible in transcription many aspects of manuscript which would otherwise pose the necessity of choosing between maximum fidelity and maximum legibility. The consequence is that a typical letter transcription in plain text, though obviously not a replacement for the original, can still be read, relied on, and quoted from, as if it were the original.

While the notation system is admittedly new, it makes as much use as possible of editorial conventions that are familiar, traditional, and old. We have, for instance, deliberately kept the number of new conventions to a minimum, modifying or adding to them only very gradually, and only as the letters themselves demand it. When editorial conventions are new, they often adapt familiar conventions of both handwriting and typography. New conventions are in general called for by the effort to include, or at least to include more legibly, what has tended to be problematic, or simply ignored, in earlier methods of transcription. Two examples here will suffice. To transcribe printed letterhead in a way that is practical, inclusive, and fully intelligible, plain text uses extra-small small capitals for the printed words and a dotted underscore below whatever the writer put in the printed blanks, such as the date and place. Likewise, to transcribe all cancellations and identify all insertions (even of single characters) where they occur in the text, but without making the result illegible, plain text uses line-through cross-out rules, a slashes, and inferior carets. ,

Most of these devices could, in 1988, be produced with the type itself, making them economical both to set and to print. And many could fairly be characterized as type-identical with their handwritten counterparts. A line or a slash through type, crossing it out, needs no interpretation: it simply means canceled, just as it would in manuscript. The overall effect therefore contrasts favorably with the effect of arbitrary symbols commonly used in “genetic text,” such as <pointed> brackets to the left <a> and right, ↑ arrows, ↓ | bars ↑, ↓ and so on—editorial conventions that today will seem both new and numerous, that will almost certainly mean something different from one edition to the next, and that in any case must be consciously construed at each occurrence. Almost all of these devices have been successfully reproduced for these electronic texts, but where that has proved impossible, we have almost always found a simple but legible replacement for them. To replace the oval border that helped signify transcribed monograms, for instance, we render the italic small capitals in blue. A few editorial signs, however, we have not successfully replaced: hairline rule for so-called mock cancellations, for example, is not visibly distinct on the computer screen, and therefore looks exactly like an ordinary cancellation. We have yet to find a solution for this problem, but fortunately most mock cancellations are self-evident or have been identified in the notes.

A related risk of type-identical signs, on the other hand, is that their editorial function as signs will be forgotten—that they will be seen to picture, rather than to transcribe (re-encode), the original manuscript. It thus bears repeating that plain text, despite its greater visual resemblance to the handwritten originals, is emphatically not a type facsimile of them, nor is it designed just to look like the original document. Like all diplomatic transcription except type facsimile, plain text does not reproduce, simulate, or report the original lineation, pagination, or any other formal aspect of the manuscript, save where the writer intended it to bear meaning and that meaning is transcribable—which is exactly why it does reproduce or simulate many formal elements, such as various kinds of indention and purposeful lineation. In fact, it is usually the case that these formal (nonverbal) aspects of manuscript already have more or less exact equivalents in nineteenth-century typographical conventions.

Clemens’s letters lend themselves to such treatment in part because his training as a printer (1847–53) gave him a lifelong fascination with all typographical matters, and in part because he lived at a time when the equivalents between handwriting and type were probably more fully developed and more widely accepted than they had ever been before (or are likely ever to be again). The consequence for his handwritten letters was that, while he clearly never intended them to be set in type, he still used the handwritten forms of a great many typographical conventions as consistently and precisely in them, as he did in literary manuscripts that were intended for publication. This habitual practice makes it possible to transcribe his letters very much as if they were intended for type—to use, in other words, the system of equivalents employed by nineteenth-century writers to tell the typesetter how the manuscript should appear in type—but in reverse, to tell those who rely on the typographical transcription just how the letter manuscript appears. In short, Clemens’s typographical expertise makes his letters easier to transcribe fully and precisely, as well as easier to read in transcription, than they otherwise would be, assuming that we understand the meaning of his signs and the code for their typographical equivalents exactly as he did—an assumption that cannot always be taken as granted.

1. The Author’s Signs

A few of the typographical signs in these letters may seem a bit unfamiliar, if not wholly exotic. Others may seem familiar, even though they in fact no longer have the precise and accepted meaning they had when Clemens used them. Especially because some signs have fallen into disuse and (partly for that reason) been adapted by modern editors for their own purposes, it is the more necessary to emphasize that here they bear only the meaning given them by Clemens and his contemporaries. Purely editorial signs in the transcription are identified and defined in a section always accessible from the top of the note pane, and since they sometimes adapt typographical conventions, they must not be confused with authorial signs. They have, in fact, been chosen to help avoid such confusion, and especially to avoid usurping the normal, typographical equivalents for authorial signs.

Still, authorial signs present two related but distinct problems for successful transcription: (a) how to explicate those signs whose authorial meaning differed from the modern meaning, but can still be recovered, at least in part; and (b) how to represent authorial signs whose earlier typographical equivalent, if any, remains unknown—at least to the editors. The glossary of Special Sorts and table of Emphasis Equivalents which follow here are intended to solve these problems—to alert the reader to those changes in meaning which we can identify, and to describe the handwritten forms for which the typographical forms are taken to be equivalent—or, in a few cases, for which they have been made equivalent because we lack a better alternative.

The glossary includes signs that do not appear in every letter, of course, and it omits some signs that will be added only as they become relevant, as letters from later years are edited. Like the glossary, the table provides some information that was, and often still is, regarded as common knowledge, which may explain why the contemporary equivalent for some authorial signs has proved so elusive. That no table of comparable detail or completeness has so far been found in any grammar, printer’s handbook, dictionary, or encyclopedia, would appear to indicate that the system of emphasis was almost completely taken for granted, hence rarely made fully explicit or published, even by those who relied upon it. The particular meaning for Clemens of all such equivalents between manuscript and type, at any rate, has had to be deduced or inferred from the letters themselves, and from his numerous literary manuscripts, with his instructions for the typist and typesetter (sometimes with the further evidence of how they responded to his instructions), as well as from the consistent but usually partial evidence in a variety of printer’s handbooks, encyclopedias, manuals of forms, and other documents bearing on what we take to be the system of equivalents between handwriting and type.3

Special Sorts

Always called “stars” by Clemens and by printers generally, asterisks appear in his

manuscript as simple

“Xs” or crosses (X), or in a somewhat more elaborate variant of the cross ( ), often when used singly. In letters (and elsewhere) he used the asterisk as a standard

reference

mark, either to signal his occasional footnotes, or to refer the reader from one part

of a text to another part. (The conventional

order of the standard reference marks was as follows: *, †, ‡, §, ‖,

¶, and, by the end of the century, ☞.) He also used asterisks for a kind of ellipsis

that was then standard

and is still recognizable, and for one now virtually obsolete—the “line of stars”—in

which evenly spaced asterisks occupy a line by themselves to indicate a major omission

of text, or—for Clemens, at any

rate—the passage of time not otherwise represented in a narrative. For the standard

ellipsis, we duplicate the number of

asterisks in the source, thus: * * * * (see also ellipsis,

below). In transcribing the line of stars, however, the exact number of asterisks

in the original becomes irrelevant, since the

device is intended to fill the line, which is rarely the same length in manuscript

as it is in the transcription. The line of stars

in the original is thus always transcribed by seven asterisks, evenly separated and

indented from both margins, thus:

), often when used singly. In letters (and elsewhere) he used the asterisk as a standard

reference

mark, either to signal his occasional footnotes, or to refer the reader from one part

of a text to another part. (The conventional

order of the standard reference marks was as follows: *, †, ‡, §, ‖,

¶, and, by the end of the century, ☞.) He also used asterisks for a kind of ellipsis

that was then standard

and is still recognizable, and for one now virtually obsolete—the “line of stars”—in

which evenly spaced asterisks occupy a line by themselves to indicate a major omission

of text, or—for Clemens, at any

rate—the passage of time not otherwise represented in a narrative. For the standard

ellipsis, we duplicate the number of

asterisks in the source, thus: * * * * (see also ellipsis,

below). In transcribing the line of stars, however, the exact number of asterisks

in the original becomes irrelevant, since the

device is intended to fill the line, which is rarely the same length in manuscript

as it is in the transcription. The line of stars

in the original is thus always transcribed by seven asterisks, evenly separated and

indented from both margins, thus:

* * * * * * *

Clemens drew the brace as a wavy vertical line that did not much resemble the brace in type, except that it clearly grouped two or three lines of text together. He drew braces intended for three or more lines as straight (nonwavy) lines with squared corners, like a large bracket, usually in the margin. He occasionally used the two- and three-line braces in pairs, vertically and horizontally, to box or partly enclose one or more words, often on a single line. The one-line brace ({ }) was evidently not known to him, and would probably have seemed a contradiction in terms. It appears to be a modern invention, but has sometimes proved useful in the transcription when the original lineation could not be reproduced or readily simulated (see SLC to Orion Clemens, 9 June 62). Otherwise, the transcription always uses a two- or three-line brace and preserves, or at least simulates, the original lineation.

dashes –—

—————

====

Clemens used the dash in all four of its most common typographical forms (one-en, one-em, two-em, and three-em), as well as a parallel dash, usually but not invariably shorter than an em dash. The parallel dash appears to be used interchangeably with the much more frequently used em dash, but almost always at the end of a line (often a short line, such as the greeting). Its special meaning, if any, remains unknown. Clemens occasionally used dashes visibly longer than his em dash, presumably to indicate a longer pause: these are transcribed as two-, three-, or (more)-em dashes, by relying on the length of em dashes in the manuscript as the basic unit. That Clemens thought in terms of ems at all is suggested by his occasional sign for a dash that he has interlined as a correction or revision (|—|), which was then the standard proofreader’s mark for an em dash. Clemens used the dash as terminal punctuation only to indicate abrupt cessation or suspension, almost never combining it with a terminal period. Exceptions do occur (SLC to Olivia L. Langdon, 26 and 27 Jan 69), but most departures from this rule are only apparent or inadvertent. For instance, Clemens frequently used period and dash together in the standard typographical method for connecting sideheads with their proper text (‘P.S.—They have . . .’), a recognized decorative use of period-dash that does not indicate a pause. The em, two-em and, more rarely, the en and the parallel dash were also used for various kinds of ellipsis: contraction (‘d—n’); suspension (‘Wash=’); and ellipsis of a full word or more (‘until ——.’). Despite some appearance to the contrary, terminal punctuation here again consists solely in the period. On the other hand, Clemens often did use the period and dash combined when the sentence period fell at the end of a slightly short line in his manuscript (‘period.— | New line’), a practice copied from the typographical practice of justifying short lines with an em dash. These dashes likewise do not indicate a pause and, because their function at line ends cannot be reproduced in a transcription that does not reproduce original lineation, are always emended, never transcribed. Clemens used en dashes in their familiar role with numerals to signify “through” (‘Matt. xxv, 44–45’). And he used both the em dash and varying lengths and thicknesses of plain rule—in lists, to signify “ditto” or “the same” for the name or word above, and in tables to express a blank. See also ellipsis and rules, below.

ellipsis ----- ...... ****

– – – – – – – — — — —

Nineteenth-century typography recognized an enviably large variety of ellipses (or leaders, depending on the use to which the device was being put). Clemens himself demonstrably used hyphens, periods, asterisks, en dashes, and em dashes to form ellipses or leaders, in his letters and literary manuscripts. The ellipsis using a dash of an em or more is also called a “blank” and may stand for characters (‘Mr. C—’s bones’) or a full word left unexpressed. In the second case, the dash is always separated by normal word space from the next word on both sides (‘by — Reilly’), thereby distinguishing it from the dash used as punctuation (‘now—Next’), which is closed up with the word on at least one side, and usually on both (‘evening—or’). When any of these marks are used as leaders, the transcription does not necessarily duplicate the number in the manuscript, using instead only what is needed to connect the two elements linked by the leaders. But for any kind of ellipsis except the “line of stars” (see asterisks), the transcription duplicates exactly the number of characters used in the original.

fist

☞ ☜

Clemens used the “fist,” as it was called by printers (also “hand,” “index,” “index-mark,” “mutton-fist,” and doubtless other names), not as the seventh of the standard reference marks, but for its much commoner purpose of calling special attention to some point in a text. As late as 1871 the American Encyclopaedia of Printing characterized the device as used “chiefly in handbills, posters, direction placards, and in newspaper work,”4 but Clemens used it often—and without apology—in his letters. We transcribe it by a standard typographical device, either right- or left-pointing, as appropriate, except in special circumstances. The following case, for instance, requires facsimile of the original, since Clemens clearly meant to play upon the term “fist” by drawing the device as a distinctly open hand:

“Put it there, Charlie!” (SLC to Olivia L. Langdon, 12

Dec

68)

“Put it there, Charlie!” (SLC to Olivia L. Langdon, 12

Dec

68)

paragraph ¶

The paragraph sign is both a mark of emphasis and the sixth of the reference marks. It is actually “P” reversed (left for right, and white for black) to distinguish it from that character. Clemens, however, commonly miswrote it as a “P,” drawing the hollow stem with large, flat feet, but not the left/right or white/black reversal in the loop. Whenever the sign is used in a letter, we transcribe it by the standard typographical device, with a record of emendation when it has been misdrawn. Clemens used the paragraph sign as a reference mark and as shorthand for the word “paragraph,” but most commonly in letters to indicate a change of subject within a passage, one of its original meanings. When he inserted the paragraph sign in text intended for a typesetter, he was doubtless specifying paragraph indention. But when he used it in a letter, he was usually invoking that original meaning. The transcription always uses the sign itself, even when it was inserted (¶) or was manifestly an instruction to a typesetter. In the textual commentary, however, the paragraph sign in brackets ¶ is editorial shorthand for “paragraph indention.”

Double rules (a), parallel rules (b), and plain rules (c), or rule dashes, in manuscript are usually, but not invariably, centered on a line by themselves, serving to separate sections of the text. When used within a line of text, they are positioned like an ordinary em dash and may serve as a common form of ellipsis, or to mean “ditto,” or simply to fill blank space in a line. This last function may be compared with the original purpose of the eighteenth-century flourish, namely to prevent forged additions in otherwise blank space. But as with the flourish, this function had in Clemens’s day long since dissolved into a mainly decorative one. Rules appear in Clemens’s manuscript in three distinguishable species, each with two variant forms. We construe wavy lines in manuscript as “thick” rules, and straight lines as “thin” rules, regularizing length as necessary. (a) Double rules appear in manuscript as two parallel lines, one wavy and the other straight, in either order. (b) Parallel rules appear in manuscript as two parallel lines, either both wavy or both straight (thick or thin). (c) Plain rules appear as single lines, either wavy or straight (thick or thin).

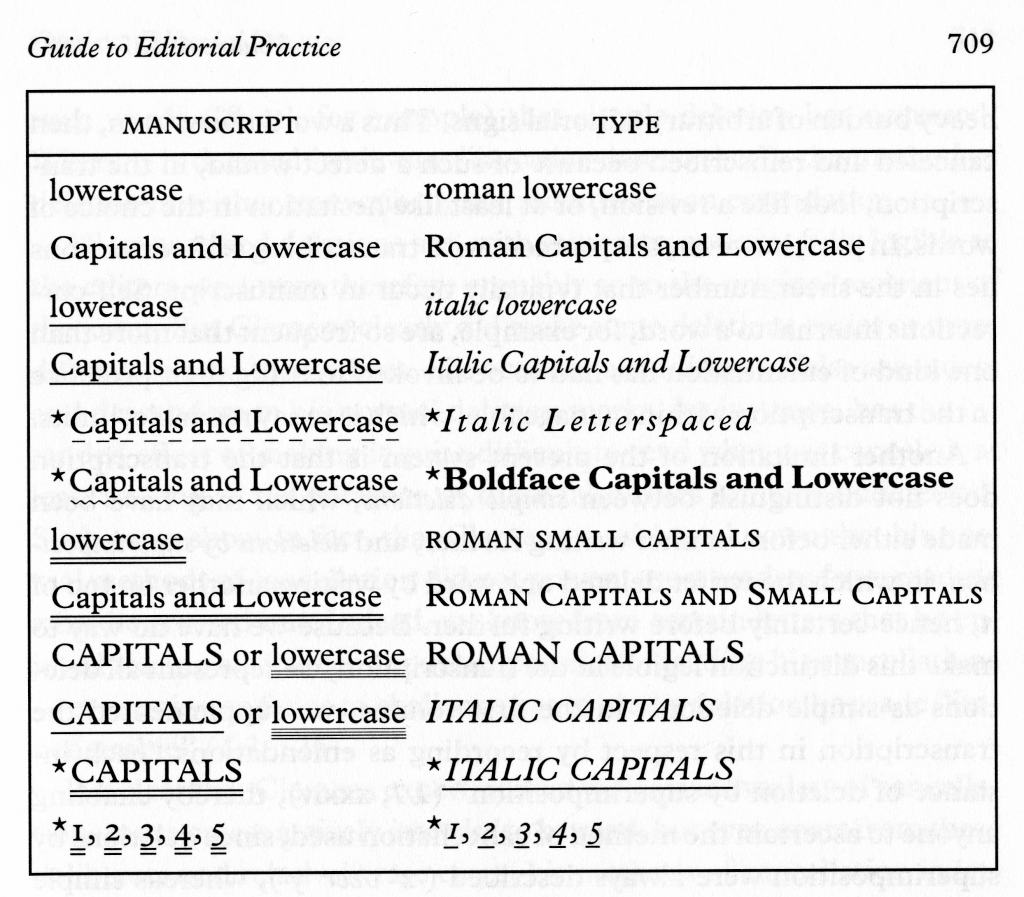

Emphasis Equivalents

Clemens used the standard nineteenth-century system of underscoring to indicate emphasis, both within and between words. He indubitably understood the equivalents in type for the various kinds of underscore, but even if he had not, they could probably be relied on for the transcription of his underscored words, simply because the handwritten and the typographical systems were mutually translatable. Although we may not understand this system as well as Clemens apparently did, it is still clear that he used it habitually and consistently, and that anomalies are much more likely to result from our, rather than his, ignorance or error.

Occasionally Clemens used what appear to be two variations of a single underscore—a broken underscore (not prompted by descenders from the underscored word) and a wavy underscore (more distinctly wavy than normally occurs with any hand-drawn line). If these are in fact variations of a single underscore, they evidently indicate a more deliberate, or a slightly greater, emphasis than single underscore would imply. They have been transcribed in letterspaced italic and boldface type, respectively, even though we do not know what, if any, typographical equivalent existed for them (both are marked * in the table). Clemens occasionally used letterspacing, with or without hyphens, as an a-l-t-e-r-n-a-t-i-v-e to italic, but he seems not to have combined it with italic, so that this editorial combination may always signify broken underscore. Wavy underscore in manuscript prepared for a printer did mean boldface, or some other fullface type, at least by 1900, but it is not clear for how long this convention had been in place. And in any case, boldface would now ordinarily be used for a level of emphasis higher than CAPITALS or ITALIC CAPITALS, so that the use of boldface type to represent wavy underscore is necessarily an editorial convention.

Clemens also sometimes emphasized capital letters and numerals in ways that appear to exceed the normal limits of the typographical system as we know it. For instance, when in manuscript the pronoun ‘I’ has been underscored twice, and is not part of an underscored phrase, we do not know what typographical equivalent, if any, existed for it. Since the intention is clearly to give greater emphasis than single underscore, rendering the word in small capitals (i) would probably be a mistake, for that would indicate less emphasis than the absence of any underscore at all (I). In such cases (also marked * in the table), we extend the fundamental logic of the underscoring system and simulate one underscore for each manuscript underscore that exceeds the highest known typographical convention. ‘I’ in manuscript is therefore transcribed as an italic capital with one underscore ( I ). Otherwise, underscores in the original documents are simulated only (a) when Clemens included in his letter something he intended to have set in type, in which case his instructions to the typesetter must be reproduced, not construed, if they are to be intelligibly transcribed; and (b) when he deleted his underscore, in which case the transcription simulates it by using the standard manuscript convention for deleting an underscore.

Since underscores in manuscript may be revisions (added as an after-thought, even if not demonstrably so), one virtue of the system of equivalents is that it allows the transcription to encode exactly how the manuscript was marked without resorting to simulation. There are, however, some ambiguities in thus reversing the code: for example, a word inscribed initially as ‘Knight’ or ‘knight’ and then underscored three times would in either case appear in type as ‘knight’. Clemens also sometimes used block or noncursive capitals or small capitals, simulating ‘KNIGHT’ or ‘knight’, rather than signaling them with underscores. Ambiguities of this kind do not affect the final form in the text, but whenever Clemens used block or noncursive letters, or when other uncertainties about the form in the manuscript arise, they are noted or clarified in the record of emendations.

†The table above is a scanned image that appears in L6, p. 709.

2. Revisions and Self-Corrections

The transcription always represents authorial revisions where they occur in the text, just as it does all but the most ephemeral kinds of self-correction. Either kind of change is wholly given in the transcription, except when giving all details of an individual occurrence or all cases of a particular phenomenon would destroy the legibility of the transcription. For revisions, the transcription always includes at least the initial and the final reading, with intermediate stages (if any) described in the record of emendations. But in letters, revisions are rarely so complicated as to require this supplemental report.

Self-corrections are sometimes omitted by emendation, and are more frequently simplified by emendation than are revisions, chiefly because if fully transcribed in place they often could not be distinguished from revisions, except by consulting the textual commentary—even though the distinction is perfectly intelligible in the original letter. This limitation comes about in part because causal evidence of errors, such as a line ending (“misspel- | ling”) or a physical defect in the pen or paper, cannot be represented in the transcription without adding a heavy burden of arbitrary editorial signs. Thus a word miswritten, then canceled and reinscribed because of such a defect would, in the transcription, look like a revision, or at least like hesitation in the choice of words. In part, however, the problem with transcribing self-corrections lies in the sheer number that typically occur in manuscript. Self-corrections internal to a word, for example, are so frequent that more than one kind of emendation has had to be invoked to bring their presence in the transcription within manageable, which is to say readable, limits.

Another limitation of the present system is that the transcription does not distinguish between simple deletions, which may have been made either before or after writing further, and deletions by superimposition, in which the writer deleted one word by writing another on top of it, hence almost always before writing further. Because we have as yet no way to make this distinction legible in the transcription, we represent all deletions as simple deletions. In 1988 (with the first printed volume of Mark Twain’s Letters) we supplemented the transcription in this respect by recording as emendations “each instance of deletion by superimposition” ( L1 , xxxiv), thereby enabling anyone to ascertain the method of cancellation used, since deletions by superimposition were always described (‘x’ over ‘y’), whereas simple deletions were not. The advantage of this procedure was that, while clumsy and expensive, it meant the transcription with its apparatus could always be relied on to indicate the method of cancellation, whether or not the editors thought this information was useful in any given case. Its great disadvantage was that it caused the record of emendations to be nearly overwhelmed by reports of superimposition, only a small percentage of which were of any interest.

Pending the invention of an affordable, reliable way to signal this distinction in the transcription, subsequent volumes record deletion by superimposition only when it is judged to be useful information—chiefly where the timing of a cancellation can be established as immediate from this evidence in the manuscript, although in the transcription the timing appears indeterminate. For example, where the transcription reads ‘Dont you’, the manuscript might show either (a) that ‘you’ followed ‘Dont’ (a simple deletion, hence indeterminate), or (b) that ‘you’ was superimposed on ‘nt’ (deletion by superimposition, hence certainly immediate). Since the record of emendation gives only those cases where cancellation by superimposition establishes the immediate timing of a change, and only where this fact is deemed relevant, readers are entitled to infer from the absence of an entry for two such words (‘& at’, for example) that simple deletion has occurred. Where it is deemed irrelevant (‘in order that so that’), the method of deletion is neither transcribed, nor recorded as an emendation.

All transcribed deletions are, with minor exceptions, fully legible to the editors, and were therefore arguably so to the original recipient of the letter. But Clemens clearly did make some deletions easier or more difficult to read than others. His occasional addition of false ascenders and descenders to his normal deletion marks, for instance, has the intended effect of making it quite difficult to read what was canceled, at least so long as the presence of these false clues remains undetected. Such cases show, in fact, that Clemens must have known that his normal methods of cancellation did not prevent most readers from reading what he crossed out. Indeed, we know from certain letters that he enjoyed teasing his fiancée about her practice of reading his cancellations—even going so far as to challenge her to read a deletion he made “impenetrable” (SLC to Olivia L. Langdon, 28 Feb 69).

It is clear that Clemens experimented with a wide variety of cancellations more or less actively intended to be read, but even apart from these deliberate and relatively rare cases, his methods of cancellation in letters ranged across a full spectrum of difficulty. The transcription does not, however, attempt routinely to discriminate among these, simply because we lack any conventional means for representing the differences legibly. Cancellations thus actively intended to be read—or not, as the case may be—are identified in the notes when their special character is not otherwise apparent from the transcription. But deletions accomplished by unusual methods are simulated whenever possible, for the methods themselves often convey some such intention (see, for example, SLC to Olivia L. Langdon, 6 and 7 Sept 69). And in some letters, Clemens used two methods of cancellation which occupy opposite ends of the spectrum of difficulty.

Mock, or pretended, cancellations are words crossed out so lightly that they are easily read, visibly distinct from normal deletions, as well as being (for the most part) deletions of words still necessary to the sense. Clemens used various methods for creating mock cancellations, but the current rendering does not distinguish them. Clemens also deleted parts of some letters by tearing away portions of the manuscript page, which he then sent, visibly mutilated. By their very nature, such deletions are unlikely to be read by anyone, but occasionally Clemens left enough evidence in the torn page to permit as much as the first or last line of the suppressed passage to be reconstructed. Yet even if the entire excision somehow survived, it would not be included in the transcription, simply because it was not part of the letter he sent. When text canceled in this fashion can be reconstructed, therefore, it may be transcribed with wholly missing characters as diamonds and partly missing characters as normal alphabetical characters, bracketed as interpolations: ‘I j◇◇◇ ros◇ ◇p &’ (SLC to Olivia L. Langdon, 27 Feb 69). The result is not, in the ordinary sense, readable—any more than the original manuscript at this point was, except where one or two characters or words left standing could still be read, out of context. The fully legible reconstructed reading is, therefore, given only in the notes.

It may be added here that some deletions in manuscript, especially of punctuation, were indicated there only by methods not themselves transcribable. For instance, when Clemens added a word or more to a sentence already completed, he rarely struck out the original period. Instead, he signaled his intention simply by leaving only the usual word space between the original last word and the first word of his addition, rather than the larger space always left following a sentence period. Whenever someone reading the manuscript would have understood something as canceled, even though it was not literally struck out, the transcription represents it as if it had been deleted in the normal fashion, and the record of emendations reports the fact as an implied deletion.

Deletions

■ Single characters and underscores are deleted by slash marks—even when the deletion is internal to the final form of the word (‘priviledge’). Single characters include the symbol for illegible character (◇) and, more rarely, Clemens’s own deleted caret (‸), when that alone testifies to his having begun a change.

. , ; : ( ) “ ” ‘ ’ ! ? — – a b c d j k l v w x y z 1 2 3 4 ◇ A B C D E F G H I J K L M N O P Q R S T U V W X Y Z $ &■ Two or more characters are deleted by a horizontal rule (‘have written’)—even when they are internal to the word (‘examinedation’).

■ Separate, successive deletions of two or more characters are signified by gaps in the horizontal rule (‘that dwell in all the hearts’). These gaps never coincide with line ends in the transcription. Thus, horizontal rules that continue from the end of one line to the next (‘I am sorry the idea occurs to me so late, but that, of course, is of no real consequence.’) always signify a single, continuous deletion, never separate ones.

■ Deletions within deletions are shown by combining the horizontal rule with the slash mark for single characters (‘though t’), or two horizontal rules for two or more characters (‘I was sail’). The earlier of the two deletions is always represented by the shorter line: to read the first stage, mentally peel away the longer line, which undeletes the second stage.

Insertions

■ Insertions are defined as text that has been placed between two previously inscribed words or characters, or between such a word or character and a previously fixed point (such as the top or the edge of the page), thus written later than the text on either side of it. Insertions may be interlined (with or without a caret), squeezed in, or superimposed on deleted characters—methods not distinguished in the transcription and not recorded as emendations except when pertinent.

■ Single characters (including punctuation marks) are shown inserted by a caret immediately beneath them (‘& I desire’).

■ Two or more characters are shown inserted, either between words or within a word, by a pair of carets (‘into’).

Insertions with Deletions

■ Insertions may be combined with deletions of one or more words, and in various sequences:

‘Eighteen months A short time ago’

‘intended to say, Aunt Betsey, that ’

■ Insertions may be combined with deletions within a word:

‘m May-tree’

‘wishes ing’

In the last two cases here, the carets indicating insertion designate characters that have been superimposed on the characters they delete. Superimposition is, in such cases, a kind of insertion designed to place new characters next to older, standing characters. Clemens might have achieved much the same thing, albeit with greater trouble, by crossing out the old and literally interlining the new characters. The timing of insertions combined with deletions internal to a word must, in any case, be understood as pertaining only to the sequence of change to that word, not as later than any other part of the text.

Beginning with letters from 1874, we depart from the practice applied to all previous Letters volumes by routinely including in the text all deletions and insertions internal to a word, regardless of whether the rejected form was a genuine misspelling, or the start of a possible word in context. The reader will therefore encounter forms like ‘imnaccuracies’ and ‘peculiaritsies’ (SLC to Edgar Wakeman, 25 Apr 74) somewhat more frequently than in the past. But to ensure that these forms do not seriously interfere with legibility, the editor still has the option to simplify them whenever Clemens reused three or fewer characters (counting quotation marks, parentheses, dollar signs, and the like). As before, the simplified form gives the original and the altered form in succession, just as if they had been separately inscribed, and the unsimplified form appears only in the textual apparatus. Thus the editor may transcribe ‘and any’ for what could more literally be rendered as ‘any d’ or ‘andy’—forms used to record the editorial simplification as an emendation. To avoid ambiguity in transcribing internally altered numerals of more than one digit, we always simplify the original form in this way.

To quote the letters without including the author’s alterations, omit carets and crossed-out matter, closing up the space left by their omission. Compound words divided at the end of a line in the print edition used the double hyphen (=) if and only if the hyphen was to be retained. The double hyphen has not been used in this new edition because (with some exceptions) the lines of text are not coded as lines, and so ambiguous hyphenation at line ends is unpredictable. There remains a statistically small chance that a hyphenated compound word that might be spelled either way, but here should be spelled with the hyphen, will occur at a line end in the transcription. But in this current iteration of the letter texts, we have found no way to tell the user how to resolve that slight ambiguity in his quotation.

3. Emendation of the Copy-Text

We emend original documents as little as possible, and nonoriginal documents as much as necessary, but we emend both kinds of copy-text for two fundamental reasons: to avoid including an error, ambiguity, or puzzle that (a) is not in the original, or (b) is in the original, but cannot be intelligibly transcribed without altering, correcting, resolving, or simplifying it.

Errors made by the writer are not emended so long as they can be intelligibly transcribed. Some few errors of omission may be corrected by editorial interpolation—that is, by supplying an intended but omitted character, word, or words within editorial square brackets, ‘thus’ or ‘“thus”’—but only when the editor is confident that the writer has inadvertently omitted what is thus supplied. Interpolated corrections may be necessary to construe the text at all, let alone to read it easily, and would therefore be supplied by any reader if not supplied by the editor. They are thus a logical extension of the decision to transcribe errors when (and only when) they can be intelligibly transcribed. Interpolated corrections do not conceal the existence of error in the original, and are therefore not emendations of it: like editorial description, or superscript numbers for the notes, they are always recognizably editorial, even when they enclose a conjecture for what the writer meant to but did not, for whatever reason, include in the letter sent. Interpolations are therefore not normally recorded in the textual commentaries. Interpolations are not always supplied, even if what is missing seems beyond serious doubt, nor could they be used to correct all authorial errors of omission: mistaken ‘is’ for ‘it’, for example, or a missing close parenthesis that must remain missing because it might belong equally well in either of two places.

Most errors in a nonoriginal copy-text, such as a contemporary newspaper, are attributable not to the writer, but to the typesetter, and are therefore emended. Yet even here, certain grammatical errors and misspellings may be recognizably authorial, and therefore not emended. On the whole, however, Clemens’s precise and meticulous habits, which were well known in editorial offices even before he left the West, make it more rather than less likely that errors in such a printing are the typesetter’s—especially because editors and typesetters were typically committed by their professions not to a literal transcription, but to a “correct” form of any document they published. Typesetting errors are self-evident in such things as transposition (‘strated’ for ‘started’), wrong font (‘carriEd’), and some kinds of misspelling (‘pouud’). In addition, we know that by 1867 Clemens consistently wrote ‘&’ for ‘and’ in his letters—except where the word needed to be capitalized, or the occasion was somewhat more formal than usual (for example, see SLC to Charles Warren Stoddard, 27 April 67). In any nonoriginal copy-text, therefore, ‘and’ is sure to be a form imposed by the typesetter, who had good professional reasons for excluding ‘&’ as an unacceptable abbreviation. The word is therefore always emended as an error in nonoriginal copy-texts.

But if authorial errors are preserved uncorrected, it may well be asked why it is ever necessary to emend originals to avoid including them, not to mention how this can be done without changing the meaning of the original letter, and therefore the reliability of the transcription.5 The general answer to these questions is that in a transcription which does not reproduce the text line for line with the original, some forms in the original must be changed if they are not to assume a different meaning in the transcription—in other words, if they are not to become errors in it. Clemens’s characteristic period-dash combination at the end of a line is a classic example of something that must be emended because it would become an error if literally transcribed. The period-dash apparently combined as terminal punctuation in Clemens’s manuscripts virtually always occurs at a line end, at least until about the mid-1880s, when he seems to have trained himself not to use the dash there, probably because contemporary typesetters so often misinterpreted his manuscript by including it in the type, where it would appear as an intralinear dash between sentences. The typographical origin of this device was probably as an inexpensive way to justify a line of type (especially in narrow measure, as for a newspaper), but Clemens would certainly have agreed with the majority view, which frowned upon the practice.6 As already suggested (see ‘dashes’ above), when Clemens used a dash following his period, he indicated simply that the slightly short line was nevertheless full, and did not portend a new paragraph. The device may owe something to the eighteenth-century flourish used to prevent forged additions in otherwise blank space, since it sometimes occurs at the end of short lines that are followed by a new paragraph. At any rate, he never intended these dashes to be construed as punctuation. Yet that is precisely what happens if the typesetter or the reader does not recognize the convention and reads it as a normal dash, signifying a pause. Any dash following terminal punctuation at the end of a line is therefore not transcribed, but emended. When ‘period.— | New line’ occurs in a newspaper or other transcription of a lost letter, it doubtless reflects the typesetter’s own use of this method for right justification, and is necessarily emended. And when ‘period.—Dash’ occurs within a line in such a printing, it is almost certainly the result of the typesetter’s misunderstanding the convention in Clemens’s manuscript, and is likewise emended.

Ambiguities left by the writer are also not emended if they can be intelligibly transcribed. But both original and nonoriginal copy-texts will inevitably contain ambiguous forms that, because the transcription is not line for line, must be resolved, not literally copied. Ambiguously hyphenated compounds (‘water-|wheel’), for example, cannot be transcribed literally: they must be transcribed unambiguously (‘waterwheel’ or ‘water-wheel’), since their division at a line end cannot be duplicated. Using the editorial rule ( | ) to show line end would introduce a very large number of editorial signs into the text, since consistency would oblige the editor to use the symbol wherever line endings affected the form in the transcription. Even noncompound words divided at the end of a line may sometimes be ambiguous in ways that cannot be legibly preserved in the transcription: ‘wit-|ness’ in the copy-text must be either ‘witness’ or ‘witness.’ Dittography (of words as well as punctuation) likewise occurs most frequently at line ends—physical evidence that makes it readily intelligible as an error in the source, but that is lost in a transcription which abandons the original lineation. Dittography becomes more difficult to construe readily when it is simply copied, because the result is at least momentarily ambiguous. It is therefore emended, even in intralinear cases, in order not to give a distorted impression of this overall class of error. The general category of manuscript forms affected by their original position at line ends, however, is even larger than can be indicated here.

Puzzles created by the writer are likewise preserved if they can be intelligibly transcribed. On the other hand, we have already described several aspects of the author’s alterations in manuscript which would, if transcribed, introduce puzzles in the transcription: the method of cancellation, errors with a physical cause, implied deletions, self-corrections that would masquerade as revisions, and changes internal to a word which the editor may simplify. These alone show that holograph manuscripts invariably contain many small details which we simply have no adequate means to transcribe.

The question posed by such details is not simply whether including them would make the text more reliable or more complete (it would), but whether they can be intelligibly and consistently included without creating a series of trivial puzzles, destroying legibility, while not adding significantly to information about the writer’s choice of words or ability to spell. There are, in fact, a nearly infinite variety of manuscript occurrences which, if transcribed, would simply present the reader with a puzzle that has no existence in the original. For instance, a carelessly placed caret, inserting a phrase to the left instead of to the right of the intended word, may be readily understood in the original, but can be transcribed literally only at the cost of complete confusion.

Exceptional Copy-Texts. When the original documents are lost, and the text is therefore based on a nonoriginal transcription of one kind or another, the normal rules of evidence for copy-text editing apply. When, however, two transcriptions descend independently from a common source (not necessarily the lost original itself, but a single document nearer to the original than any other document in the line of descent from it), each might preserve readings from the original which are not preserved in the other, and these cannot be properly excluded from any text that attempts the fullest possible fidelity to the original. In such cases, no copy-text is designated; all texts judged to have derived independently from the lost original are identified; and the text is established by selecting the most persuasively authorial readings from among all variants, substantive and accidental. Before this alternative method is followed, however, we require that the independence of the variant texts be demonstrated by at least one persuasively authorial variant occurring uniquely in each, thereby excluding the possibility that either text actually derives from the other. If independent descent is suspected, even likely but not demonstrable in this way, the fact is made clear, but whichever text has the preponderance of persuasively authorial readings is designated copy-text, and the others are treated as if they simply derived from it, whether or not their variants are published.

Damaged texts (usually, but not necessarily, the original letters) are emended as much as possible to restore the original, though now invisible, parts of the text that was in fact sent. This treatment of an original document may seem to be an exception to the general rule about emending originals as little as possible, but a damaged manuscript is perhaps best thought of in this context as an imperfect copy of the original. And despite some appearance to the contrary, emendation in such cases is still based on documentary evidence: sometimes a copy of the original made before it was damaged, or damaged to its present extent—more commonly, evidence still in the original documents but requiring interpretation, such as fragments of the original characters, the size and shape of the missing pieces, the regularity of inscribed characters (or type) and of margin formation, the grammar and syntax of a partly missing sentence, and, more generally, Clemens’s documented habits of spelling, punctuation, and diction. This kind of evidence cannot establish beyond a reasonable doubt how the text originally read. Its strength lies instead in its ability to rule out possible readings, often doing this so successfully and completely that any conjecture which survives may warrant some confidence. At any rate, we undertake such emendations even though they are inevitably conjectural, in part because the alternative is to render the text even less complete and more puzzling than it is in the damaged original (since sentence fragments are unintelligible without some conjecture, however tentative), and in part because only a specific, albeit uncertain, conjecture is likely to elicit any effort to improve upon what the editors have been able to perform. For this same reason, a facsimile of any seriously damaged document is always provided.

Letters and, more frequently, parts of letters that survive in the original but cannot be successfully transcribed constitute another exception and will be published in facsimile. For example, four letters that Clemens typed in 1874 (joking the while about his difficulties with the typewriter) clearly exceed the capacity of transcription to capture all their significant details, particularly the typing errors to which he alludes in them. Partly because they were typed, however, the original documents are relatively easy to read and therefore can be published in photographic facsimile, which preserves most of their details without at the same time making them any harder to read than the originals. These are true exceptions in the sense that most of Clemens’s typed letters can and will be transcribed. But it is generally the case that facsimile cannot provide an optimally reliable and readable text, even of Clemens’s very legible holograph letters, which comprise at least eight thousand of the approximately ten thousand known letters.

Yet by the same principles which justify transcription of most letters into type, facsimile should serve to represent within a transcription most elements of a manuscript which would (a) not be rendered more clearly, or (b) not be rendered as faithfully by being transcribed (newspaper clippings, for instance)—or that simply cannot be faithfully transcribed, redrawn, or simulated (drawings, maps, rebuses, to name just a few of the possibilities). It follows that if an original newspaper clipping enclosed with a letter cannot, for any reason, be reproduced in legible facsimile, it will be transcribed line for line in what approximates a type facsimile of the original typesetting. If the text of an enclosed clipping survives, but no example of the original printing is known, it is transcribed without simulating the newspaper format. And long or otherwise unwieldy, or doubtful, enclosures may be reproduced in a separate document.

Letters which survive only in the author’s draft, or in someone else’s paraphrase of the original, are also exceptions. In the first case, the source line of the editorial heading always alerts the reader that the text is a draft. In such cases, emendation is confined to those adjustments required for any original manuscript, and is not designed to recover the text of the document actually sent, but to reproduce the draft faithfully as a draft. Likewise, if a letter survives only in a paraphrase, summary, or description, it is included in the volume only if the nonoriginal source is judged to preserve at least some words of the original. And like the author’s draft, it is not necessarily emended to approximate the original letter text more closely, since its nonauthorial words usually provide a necessary context for the authorial words it has, in part, preserved. When it is necessary to interlard paraphrase with transcription, the paraphrase appears in italic type and within editorial brackets, labeled as a paraphrase, in order to guarantee that there will be no confusion between text which transcribes the letter and text which does not pretend to. When nonoriginal sources use typographical conventions that are never found in Clemens’s manuscripts—word space on both sides of the em dash, for instance, or italic type for roman and vice versa—the normal forms of the lost manuscript are silently restored.

Silent Emendations. In addition to the method of cancellation, which is usually omitted from the transcription and the record of emendations, several other matters may involve at least an element of unitemized, which is to say silent, change. To save space, we transcribe only routine addresses on envelopes by using the vertical rule ( | ) to signify line end; nonroutine text on envelopes is transcribed by the same principles used elsewhere. The text of preprinted letterhead is reproduced in extra-small small capitals, usually in its entirety, but as fully as possible even when unusually verbose, and never to an extent less than what Clemens may be said to adopt or refer to (‘I’m down here at the office’). Only substantive omissions from letterhead are reported as emendations, since the decorative variations of job type are literally indescribable. Postmarks are also transcribed in extra-small small capitals, but only unusual postage stamps are transcribed or described. Whenever Clemens used any of the following typographical conventions in his original letter (hence also whenever they occur in nonoriginal copy-texts and are deemed authorial), the transcription reproduces or simulates them, even when it is necessary to narrow the measure of the line temporarily, which is done silently: diagonal indention; hanging indention; half-diamond indention; squared indention; the flush-left paragraph and the half line of extra space between paragraphs, which is its collateral convention; text centered on a line, positioned flush right, or flush left; and quotations set off by quotation marks, indention, reduced space between lines (reduced leading in type), extra space above or below (or both), smaller characters in manuscript (smaller type in nonoriginals), or any combination of these conventions.

Normal paragraph indention is standardized at two ems, with variations of one em and three ems often occurring in the same letter. We silently eliminate minor, presumably unintended variation in the size of all indentions, and we place datelines, complimentary closings, and signatures in a default position, unless this position is contradicted by the manuscript, as when extra space below the closing and signature show that Clemens intended them to appear on the same line. But unmistakably large variation in the size of indention is treated as deliberate, or as an error, and reproduced or simulated, not corrected or made uniform. Notes which Clemens specifically did not insert within the letter text but wrote instead in its margin are nevertheless transcribed at the most appropriate place within the text, and identified by editorial description: ‘in margin: All well’, or ‘in bottom margin over ’. The editorial brackets in these cases may enclose just the editorial description, or both the description and the text described, depending on which conveys the original most economically. The only alternative to transcribing these notes where they are deemed “appropriate” is to transcribe them in a completely arbitrary location, such as the end of the letter. We likewise transcribe postscripts in the order they occur, even if this differs from the order they were intended to be read, so long as the intended order remains clear. Thus a marginal ‘P. P. S.’ can intelligibly precede a ‘P. S.’, just as a ‘P. S.’ inserted at the top of a letter can precede the letter proper, whether or not it was actually intended to be read first. But if, for example, a postscript inserted at the top is written across or at right angles to the main text—a sign it was not intended to be read before or with the text it crosses—the intended order must prevail over the physical order, and the postscript is therefore moved to the end of the letter. Only changes in writing media are noted where they occur in the text, as in ‘postscript in pencil’, from which it may also be reliably inferred that all preceding text was in ink. Line endings, page endings, and page numbers are silently omitted from the transcription, but where they affect the text or its emendation, they are given in the record of emendation.

4. Textual Commentaries

Each commentary usually has four sections but may have as many as five (sections are omitted when there are no facts to report). ■ Copy-text identifies the document or documents that serve as the basis for the transcription, and from which the editors depart only in the specific ways listed as emendations. ■ Previous publication cites, in chronological order, all published forms of the letter known to the editors, indicating which of these (if any) are notably incomplete or erroneous. The record of publication given here is not necessarily exhaustive, since the aim is to identify where and when a letter was first made generally accessible. Publications frequently referred to are described in the Description of Texts. ■ Provenance reports what the editors have been able to learn about an original letter’s history of ownership. Under this heading the reader may often be referred to the history of the relevant collection of manuscripts, as given in Description of Provenance. ■ Emendations and textual notes lists all deliberate departures from the copy-text (barring only changes categorized here as silent emendations). But the list may also include (a) editorial refusals to emend, identified by ‘sic’, and (b) textual notes (always italicized and within square brackets) which explain the reasoning behind particular editorial decisions to emend, or not, as the case may be. When no copy-text has been designated because two or more documents descend independently from the lost original, all variants are recorded and identified by abbreviations defined under Copy-text, and this section is renamed Emendations, adopted readings, and textual notes, to signify that variant readings have been chosen on their merits from two or more authoritative texts. ■ Historical collation lists variants between two or more nonoriginal documents that may have descended independently from a common source, but have yielded no conclusively authorial variants.

All entries in these lists begin with the reading exactly as it stands in the transcription, except where indention ¶, line ending ( | ), or abbreviation (‘Write . . . is’) is necessary. As far as possible, entries are confined to the words and punctuation being documented. Line numbers include every line of letter text on a page, even when the page contains text for more than one letter, including all rules, all enclosures, and all lines that are wholly editorial, such as ‘about one page (150 words) missing’, ‘in pencil’, the editorial ellipsis ( . . . . ), or the full-measure envelope rule. Line numbers exclude all editorial matter in the letter headings and in the notes. Each reading is separated by a centered bullet ( • ) from the corresponding reading of the copy-text, transcribed without change or emendation, insofar as our notation permits, or described within brackets and in italic type, as necessary.

Editorial Signs and Terms

| ¶ | Paragraph indention. |

| ~ | A word identical to that on the left of the bullet (hyphenated compounds are defined as one word). |

| ‸ | Punctuation absent from text to the right of the bullet. |

| ‖ | End of a line at the end of a page. |

| t◊◊t within brackets | Text within brackets is missing from, or obscured in, a damaged copy-text, and therefore

can be identified only conjecturally.

Diamonds stand for missing and invisible characters; normal characters stand for partly

visible characters; and word space is

conjectural, not actually visible. Thus the following notation shows which characters

have been emended into the copy-text, and how

they must have been configured in the undamaged original if and only

if the

conjecture is correct. 120.5–6 did not mean • di◊◊ ◊◊◊ ◊◊◊◊ torn Alternative conjectures are almost always possible, and may be more or less plausible, insofar as they too are consistent with the physical and syntactical evidence. |

| above | Interlined or written in the space above something else. Compare ‘over’ and ‘across’. |

| across | Written over and at an angle to previously inscribed text. |

| conflated | Sharing an element, usually a minim. |

| false start | Start anticipated, requiring a new beginning, as in a race. |

| implied | Understood as intended, even though not literally or completely inscribed. |

| miswritten | Malformed, misshapen—not mistaken in any other sense. |

| over | Superimposed on something, thereby deleting it. Compare ‘above’ and ‘across’. |

| partly formed | Not completed, hence conjectural. |

R. H. H.

Revised, August 2007

The transcription is not a literal text, even though it is probably as inclusive as most texts for which that claim is made, nor is it a noncritical text, as defined by G. Thomas Tanselle, since even though it “aims at reproducing a given earlier text [i.e., the original letter] as exactly as possible,” the editor essentially defines what is possible by deciding what can be transcribed legibly. The editor is therefore “making decisions about how the new text will differ from the text in the document,” with the result that the transcription necessarily “becomes a critical text” (“Textual Scholarship” in Introduction to Scholarship in Modern Languages and Literatures, edited by Joseph Gibaldi [New York: Modern Language Association, 1981], 32, 47).

According to Fredson Bowers, “General methods of transcription divide neatly in two,” which is to say (a) clear texts, with supplementary apparatus containing all details of revision, and (b) genetic texts, without supplementary apparatus because the text itself contains all such details. A clear text transcribes the revised form of a manuscript “diplomatically,” meaning that the “transcription exactly follows the forms of the manuscript in spelling, punctuation, word-division, italics (for underlining), and capitalization, but not in matters of spacing or in line-division, nor is a facsimile visual presentation of alterations attempted.” A genetic text, on the other hand, includes authorial alterations in the text “by means of a number of arbitrary symbols like pointed brackets to the left or right, arrows, bars, and so on,” with the common result that it is often “difficult to read the original text consecutively” and “impossible to read the revised text at all in a coherent sequence” (“Transcription of Manuscripts: The Record of Variants,” Studies in Bibliography 29 [1976]: 213–14, 248). Plain text, however, descends from a kind of transcription not mentioned by Bowers, in which the myriad details of a manuscript (particularly the author’s alterations to it) are systematically divided between the text and its apparatus, precisely in order to make the text as complete and informative as possible without destroying its legibility (see N&J1 , 575–84). The practical result of this division is radically improved by adopting a less obtrusive and more readable system of notation than has been used in the past: plain text manages simultaneously to increase both overall legibility and the amount of detail that can be included in the transcription.

American Encyclopaedia of Printing, edited by J. Luther Ringwalt (Philadelphia: Menamim and Ringwalt, J. B. Lippincott and Co., 1871), 217.

G. Thomas Tanselle, “Historicism and Critical Editing,” Studies in Bibliography 39 (1986): 8 n. 15.

The dash “is totally inadmissible as something to fill out a line, when that ends with a period and there is hardly enough matter” ([Wesley Washington Pasko], American Dictionary of Printing and Bookmaking [New York: Howard Lockwood and Co., 1894; facsimile edition, Detroit: Gale Research Company, 1967], 132).